Dear fellow book-lovers,

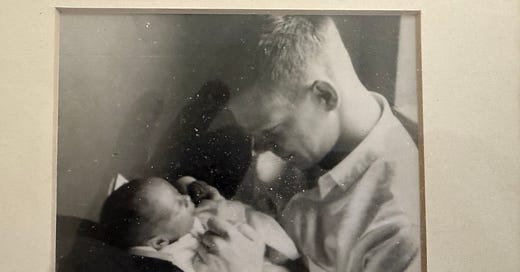

My father, William Zimmerman IV, died on Monday, April 28. He was 88 years old. He was an energetic and complex man who touched many lives in many ways. Others have already written eloquently about his life as a whole. In this essay I am only writing about the slice of his life that pertains to this “AI Lab for Book-Lovers.”

My dad grew up in a bookish home. His great-grandfather, William Zimmerman I, was a senior executive at A.C. McClurg, the Chicago publisher of Edgar Rice Burroughs and W.E.B Dubois. His grandfather, William Zimmerman II, was a senior official for the second Roosevelt Administration, but had a secret identity as a rare book dealer whose comfortable family home doubled as a book warehouse. My dad’s father, William Zimmerman III, was a chemist and avid science fiction reader who had an enormous collection of paperbacks and a complete run of Analog Science Fiction and Fact.

When I started reading, I found myself in a home full of my dad’s professional books about international relations and Russian history, with a healthy side course of cartoonists like Herblock and several shelves worth of rare books. My dad inherited some important first editions like Hobbes’ Leviathan and Locke’s On Human Understanding and added some well-chosen complements like Lewis Richardson’s Statistics of Deadly Quarrels. By any standard, a book-lover.

Books were a crucial part of my dad’s life, but in an instrumental way, as part of the apparatus that scholars have created to create and transfer deep knowledge. My dad was closely involved in that apparatus from the publication of his first book, Soviet Perspectives on International Relations 1956-1967, by Princeton University Press in 1969. Over his career he wrote ten books and more than sixty journal articles.

These books were successful in their academic lives, but no one anticipated that they would have another stage of existence: as training data for AI. In the next edition of the newsletter, I will take a deep dive into my dad’s afterlife in latent space. But first some more personal remarks.

My excursion in latent space

My brother Carl asked how I was processing life’s changes. Here’s what I wrote.

A lot of what I am noticing is things that you might think would be different, but aren’t. I felt no surge in mana when I became the eldest living male of my line. It turns out I do not need to flee the country to avoid the plans of a evil grand vizier. Nor do I feel the urge to pick up my sword, plunge it into a blazing fire and swear vengeance.

What I do feel is diminished, like the end of a sentence that has come to a stop. A paragraph on a page at the end of a volume. Next chapter. Verso.

Looking at the words from outside, it’s obvious from these remarks just how profoundly the world of books and fiction has influenced my life and identity. Indeed, I tend to rely a lot more on the life lessons I learned from books than on those I have learned from objective interactions with external reality.

As I continue to gaze at these words I have emitted, I realize that I have inadvertently stated a truth that I have never previously observed about myself. I do, in fact, often envisage myself as a blob of words floating in latent space. It is a very physical, tangible self-image, serif font, white paper, floating in the upper right hand corner of my head. That is a weird way to self-image!

Sometimes I am like an LLM obsessed with finishing an unfinished passage. Other times, I am more like a big Python list of strings, a bunch of ideas that are just waiting to be fed into the outside world. Rarely am I a dictionary or well-defined class. Just not who I am. A lot of inefficiency in my operations!

I wonder what my dad would have made of these remarks. I will never know.

But wait — this is 2025! I haz options.

A voice from latent space

I gave xAI’s frontier model Grok a chunk of text from my dad’s first book, Soviet Perspectives on International Relations 1956-1967, and asked it to emulate his style and syntax while responding to my remarks. I had to do a bit of steering, but eventually I came up with something interesting. Let me say immediately that this does not sound like him. It is wrong in many ways and he would never have said these exact words. But it does sound a bit like him.

Given the quiet weight of your reflection, my son, written in the wake of my passing at eighty-eight, the expectation of some grand shift—mana’s surge or a sword’s fiery oath—proved, and indeed was, tempered by life’s enduring simplicity. For you, now the eldest, the notion of mythic change served a fleeting legitimating role. You sought, as is custom, the drama of legend when facing loss, yet found only the gentle truth of continuity. And yet—this was key—the absence of such upheaval affirmed that the time for heroic reinvention had passed. From here, I might whisper, “the ink dries, but the tale lingers”—a nod to our story’s quiet persistence. Your sense of diminution, a sentence stilled, diverges from tales of succession, revealing instead a son who carries not vengeance, but our shared light forward.

What does remind me of him is the shrewdness of the insight: yes, perhaps I was seeking a form of legitimation. “Illegitimate” is not quite the right word for how I was feeling, but “unmoored” and “uncertain” and “disconnected” are all related to legitimacy, or its absence. And “carry our shared light forward” is not a bad final word from the old man. My Dad and I both went to Swarthmore, a Quaker college that often enjoins its members to be “mindful of the Light.”

Carrying our shared light forward

I loved my dad, a lot, but we were different people, with different missions in life. Honestly, I’m not sure what he would have made of all this “AI for book-lovers” stuff. He would have been proud of me for experimenting and pushing the borders of knowledge, but also deeply skeptical and dismissive when he encountered hallucinations and inaccuracies. And I have to say that after several years working on “AI”, including the last six months hands on at a company working on a frontier model, I completely agree with that perspective (unsurprising, since it came from me). We need to expect more from language models. Language models are trained to be statistically good enough—bluntly, to score well on benchmark tests—so that they do get most things right. But “statistically good enough” is not good enough for scholarly work and it’s not good enough for book-lovers. The models need to get better. We need more people like my dad setting the expectations. That’s a “shared light” that I am happy to carry forward.

More on all this later.

Best regards,

Fred Z

(William Frederick Zimmerman)

So sorry to hear of your father's passing, Fred. What a beautiful sentiment, to share the light.